Why I Keep Returning to the 1920s:

A Personal Reflection on Culture, Thought, and the Spirit of an Era

Illustration by Fernando Vicente ©Christie’s

Since my childhood, I have had an unexplainable affection for the 1920s, even before I first encountered the phrase “Roaring Twenties.” It is hard to define the precise timeframe. I might actually mean the period between the early 1900s and the 1930s, framed by the upheavals before and after the First World War. What draws me back to that era again and again is not simply aesthetic nostalgia, but a longing for a time when culture, ideas, and imagination seemed to pulse vividly through society.

This is not an article about the 1920s as a historical period, but a personal reflection on how that time has shaped the formation of my thought, my intellectual path and the questions I still carry.

A Childhood Without the Language for It

As a child in Hong Kong, I did not have history lessons in primary school. No one around me, neither family members nor classmates, shared my interest in history. But I discovered a world through a series of world history comic books from the school library. These simplified, visualised stories of global events, mostly Western-centred, sparked in me a kind of historical consciousness. Through them, I began to see how ways of life changed, how beliefs evolved, how people lived and thought differently across time.

Visually, the earliest impressions I had of the early 20th-century came from scattered fragments, a National Geographic magazine commemorating the Titanic’s anniversary, the film Titanic, and van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night. But my fascination was not with the romantic story, nor with the visual spectacle. What stayed with me was not a nostalgic fantasy, but the broader cultural context that surrounded those images, the sense of transition, contradiction, and richness that seemed to radiate from that period.

As I grew older, I started to notice patterns in historical development—changes in collective ideals, structures of power, and cultural expression. These were observations I made intuitively, without guidance. It was not until I began an Associate Degree and encountered philosophy and cultural studies that I realised the kinds of questions I had long been asking fell within the realm of postmodern thought: questions about change, ideology, and modernity itself. I later entered university with hopes of exploring this further. But there was no cultural studies major, and sociology was steeped in classical theories that did not speak to my concerns. Still, the questions persisted.

A Dazzling and Complex Era

I am drawn to periods of transition: times when the old world had crumbled, yet the new one had not fully taken shape. In the wake of the First World War’s devastation, old hierarchies, including aristocracy, monarchy, and inherited authority, had lost their grip, leaving a vacuum where new ideologies and possibilities emerged. These are moments where ideas are alive and fiercely debated. The 1920s were full of tensions: between tradition and modernity, inherited order and experimentation, emancipation and trauma. And yet, across those tensions, there was a cultural and intellectual radiance that still captivates me.

In Europe, the era witnessed a striking convergence of minds: Sigmund Freud and C.G. Jung redefined the psyche; Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, Ernst Cassirer, Walter Benjamin, Jean-Paul Sartre, the Vienna Circle, and the Frankfurt School reshaped the questions of modern philosophy and critical thought. In literature: Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot, Marcel Proust, Hermann Hesse. In the arts: Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Salvador Dalí. In music: Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Maurice Ravel, alongside the growing presence of jazz in Paris.

What stays with me is not simply the presence of these individuals, but the conditions that allowed so many to emerge at once. Cafés and salons in Paris became sites of conversation, contention, intellectual fermentation, spaces where aesthetic inquiry met philosophical restlessness. At Gertrude Stein’s salon, Picasso, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and others gathered for idea exchange.

And this flourishing was not confined to Europe. In China, the May Fourth era marked a cultural awakening. Figures such as Hu Shi, Lu Xun, Cai Yuanpei, Zhou Zuoren, Guo Moruo, Yu Dafu, Xu Zhimo, and the painter Xu Beihong engaged in debates over modernity, reform, aesthetics, and national identity. In India, Rabindranath Tagore reflected on the relationship between East and West. In Japan, writers like Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, and Yasunari Kawabata shaped a distinctly modern literary consciousness. The ferment was global. Newspapers and journals multiplied. People were not only reacting to crisis, they were trying to reimagine the world.

Even the bourgeoisie still held reverence for the arts, philosophy, and intellectual pursuits. Wealth was often accompanied by a sense of cultural responsibility, or at least patronage. That mix of transformation, critical energy, and intellectual depth gave the time a strange vitality.

Few moments in history have seen such a dense clustering of extraordinary minds. Across very different contexts, the 1920s brought into focus an unusual concentration of figures whose ideas would leave long shadows. That density—of questioning, creation, and imagination—feels increasingly rare.

A Different Cultural Climate

When I was young, whenever we were asked who we looked up to, the most common answers were Warren Buffett and Li Ka-shing. These names represented financial success, not creative or cultural achievement. In the past decade, names like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk became more prominent. Yes, they are inventors and visionaries, but they are also entrepreneurs. Their popularity owes much to the powerful brands they built: Apple and Tesla.

I do not mean to diminish their achievements. But it is worth asking why those we admire today are almost always linked to innovation tied to enterprise, measured by scale, profit, and dominance. In parallel, those who once shaped public discourse—writers, intellectuals, and artists—have gradually drifted to the periphery of popular culture. The most well-known public figures today are celebrities, influencers, and icons of visibility: K-pop stars, reality television personalities, the Kardashians. Where are the thinkers, the poets, the voices that shape how we understand the world?

What We Chose to Forget

Intellectual life has not disappeared, but it no longer stands at the centre of collective aspiration. It has become peripheral, replaced by a culture of visibility and consumption. Today, the most admired lives are those that scale, sell, and spread.

I often wonder whether this shift reflects a deeper transformation in values. It is not that our time lacks intelligence, but that it venerates a different kind of success. One measured by immediacy, visibility, and circulation. I am not yearning for a return to “high culture,” but for a cultural climate where reflection, focus, and depth of thought have space to breathe.

The 1920s were not perfect. Much of what blossomed belonged to elite networks; many were left out. But it was a period of intense cultural dynamism, when critical thinking, aesthetic exploration, and philosophical inquiry were not marginal activities but central to the spirit of the time.

Conclusion

Perhaps what draws me back is not nostalgia in its simple form, but a longing for the conditions that once made room for thinking, imagination, and cultural vitality. I keep returning to the 1920s because something in that moment felt possible, a culture where thinking mattered, and where creativity and ideas shaped the public imagination. It reminds me that culture can be a force of ignition—not merely a decoration, but a field where thought, feeling, and form meet to shape what is yet to come.

That moment, when ideas circulated with urgency and weight across salons, newspapers, and public debate, did not arise accidentally. It reflected a different configuration of values, where even amidst turbulence, people believed in the necessity of thinking, the beauty of form, the stakes of philosophy.

Tracing my own thoughts back to that time is not an escape into the past, but a way to mark the questions that continue to haunt the present. What kind of time are we living in now? What does it ask of us? And where, in the midst of noise, speed, and spectacle, might meaning still take root?

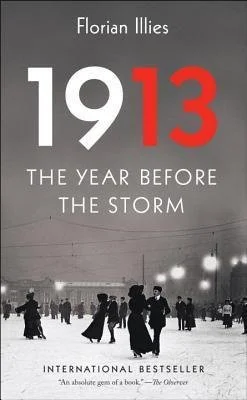

Florian Illies’s 1913: The Year Before the Storm

For those interested in the cultural texture of prewar Europe, this book offers a vivid, fragmentary portrait of the intellectual and artistic world just before everything changed.

Author’s Note

This reflection is intentionally selective. It does not aim to offer a comprehensive account of the 1920s, nor does it cover all that has popularly defined the decade. Much existing writing on this period focuses on developments in the United States: the Jazz Age, flappers, The Great Gatsby, the rise of Hollywood silent cinema, and the emergence of mass consumer culture and advertising. These are important in their own right, and they anticipated many of the dynamics that would define the post-Second World War world: spectacle, circulation, branding, and mass entertainment.

I have also chosen not to dwell on the “Lost Generation” or the Harlem Renaissance, though both were vital parts of the 1920s cultural landscape. The former, shaped by disillusionment and existential questioning, was deeply connected to the spirit of the time. Still, their story of postwar dislocation, fractured identity, and literary reinvention deserves its own space. I hope to return to it in a future reflection. The Harlem Renaissance, while equally a form of cultural dynamism, arose from a different set of historical and political conditions, rooted in the resistance, self-definition, and aesthetic innovation of African American communities. Its social and political meanings differ from the intellectual atmosphere I have tried to trace here.

Nor do I wish to overlook the devastation of the First World War, the military tensions that followed, or the economic turbulence that defined much of Europe, particularly in Britain and Germany. These realities shaped the cultural landscape in complex ways. Similarly, the 1930s brought a distinct atmosphere, one marked by the 1929 Great Depression, the rise of fascism, and the intensification of political ideologies. That is a different moment, with its own questions.

What I have tried to reflect on here is a particular moment in time, defined by an extraordinary concentration of thinkers, artists, and writers, and by a cultural climate in which questions of meaning, form, and modernity were vividly and urgently alive. It was a time of intensity, transition, and imagination, when thought and creation felt bound up with the possibility of making new worlds.