From Sally Lunn’s to Hong Kong’s Cha Chaan Tengs:

Preserving Everyday Heritage

During a short visit to Bath, England, I had lunch at Sally Lunn’s Historic Eating House & Museum, the oldest house in the city. Sally Lunn’s is renowned for its Bath Buns, first brought to Bath in 1680 by the Huguenot refugee Solange Luyon (later anglicised as Sally Lunn), and still made to her original recipe. What fascinated me most was not just the food but the model: a restaurant that is also a museum. Downstairs, you can still see the original bakery used in the 1680s. The restaurant does not just serve meals; it curates its own history, turning everyday dining into an act of cultural preservation.

It reminded me of Hong Kong’s own everyday heritage: the 茶餐廳 (cha chaan teng) and their predecessors, the 冰室 (bing sutt).

Bing Sutt and Cha Chaan Teng: A Short History

Cha chaan tengs are among the most distinctive expressions of Hong Kong’s food culture. Yet they have not been officially recognised as intangible cultural heritage.

They trace their roots to the bing sutt (冰室) that first appeared in the 1920s–30s. At that time, under British colonial rule, Western restaurants catered mainly to expatriates and elites. Prices were high; ordinary Hongkongers could not afford them. Bing sutt filled the gap by offering affordable versions of Western light meals: coffee, milk tea, red bean ice (紅豆冰), sandwiches, toast. Some even ran their own bakeries, producing pineapple buns (菠蘿包), egg tarts (蛋撻), and other iconic goods. They did not serve rice or full meals.

After the Second World War, the cha chaan teng emerged. These cafés combined bing sutt snacks with rice dishes and Cantonese cooking. They became spaces of fusion: places where East met West, where colonial influence mixed with local tastes, producing a food culture unlike anywhere else.

What They Represent

Traditional cha chaan tengs, especially the old-style bing sutt, may not offer a huge variety of food, but they record something unique to Hong Kong’s culture:

1. East–West Fusion

Hong Kong’s ‘soy-sauce Western food’ (豉油西餐) represents the localisation of foreign influence. It blended Western cooking techniques with Chinese condiments and ingredients. Some iconic examples:

叉燒湯意粉 (char siu macaroni soup): macaroni in broth topped with Chinese barbecued pork.

咖喱牛腩飯 (curry beef brisket rice): Indian curry spices fused with Cantonese beef brisket.

菠蘿包 (pineapple bun): created by adapting Chinese walnut-cookie techniques onto a soft Western bread. Despite the name, it contains no pineapple; the golden crust only resembles its skin.

2. Pace and Efficiency

Dining in a cha chaan teng mirrors the city’s tempo: quick seating, quick ordering, quick eating, quick turnover. If you want to experience the rhythm of everyday Hong Kong life, there is no better place.

A Culture Under Threat

But these places are vanishing. Since the pandemic, closures have come wave after wave.

In 2022, 美都餐室 (Mido Café) in Yau Ma Tei, opened in the 1950s and famous for its preserved décor, twice closed and reopened, sparking public outcry.

By late 2024, long-standing eateries such as 華南冰室 (Wah Nam Bing Sutt) in Sham Shui Po, 英發茶冰廳 (Ying Fat Cafe) in Kwun Tong, and 鴻運冰廳餅店 (Hung Wan Café), immortalised in films like The Lucky Guy (1998) and Election 2 (2006), all shut down for good. [Hung Wan Café was later taken over by the Tsui Wah Restaurant Group and reopened in 2025.]

Many surviving cha chaan tengs are now chain-operated, with menus and décor that have lost their authentic taste. New retro-style cafés mimic the ‘look’ of old bing sutt but with pastiche nostalgia, a random mix of vintage props turned into décor, creating a superficial ‘old Hong Kong’ aesthetic. Nostalgia becomes gimmick.

Few still run their own bakeries or serve classics like 滾水蛋 (poached egg in hot water, a post-war source of protein), 黑牛 (ice cream with cola), or 保衛爾牛肉茶 (Bovril beef tea). Even rarer are quirky Hong Kong inventions: 檸啡 (coffee with lemon), 黑白鴛鴦 (Horlicks mixed with Ovaltine), once nicknamed 兒童鴛鴦 (yuanyang for kids). These drinks are now virtually unknown to younger generations.

Tastes have also changed. Young people rarely order 鴛鴦 (yuenyeung, coffee with milk tea, — a Hong Kong invention), or 茶走 (milk tea with condensed milk), drinks beloved by older generations. With rising health consciousness and café culture, cha chaan tengs have lost their appeal as the ‘default’ choice.

Even Hong Kong’s once-iconic 凍檸茶 (iced lemon tea) has been displaced by Mainland imports like 手打檸檬茶 (hand-shaken lemon tea) and 鴨屎香檸檬茶 (duck shit fragrance lemon tea). Tourists in Hong Kong often end up at these Mainland chains, mistaking them for authentic ‘港風’ (‘Hong Kong style’) — a term mostly circulated in Mainland China. On Xiaohongshu, searching ‘港風’, yields content detached from Hong Kong’s lived culture, curated instead for Mainland audiences.

This kind of ‘Hong Kong style’ recalls Edward Said’s Orientalism: an image imagined and constructed by outsiders — in this case, by the Mainland — and projected onto Hong Kong.

In truth, Hong Kong has no such thing as ‘港風’. What we have is ‘港式’ (Hong Kong style in its own right) — and that is what is disappearing.

Pressures and Closures

In the past year, Mainland restaurants and food culture have expanded aggressively into Hong Kong. Dishes like 酸菜魚 (suan chai yu, pickled fish) and 酸辣粉 (suan la fen, hot and sour noodle) are taking over streets. From shop names to typography to interior décor, many establishments clash with Hong Kong’s original streetscape and visual culture.

Local brands are closing one after another. Even large chains. The well-known 燉奶佬 (Daniel’s Group), founded in 1981, and 海皇粥店 (Ocean Empire Food Shop), founded in 1992, both shut down all branches in 2025. 金記冰室 (Kam Kee Café), founded in 1967, has shrunk from about 40 branches at its peak to just 10 by 2025.

Responsibility and Reflection

Yes, Hong Kong has always been a place of fusion, of East meeting West. That hybridity is part of our identity. But before the streets, the tastes, and the scenes we know disappear, or pass a point of no return, we need to act.

This is not about rejecting Mainland restaurants or food cultures. What matters is diversity. The crisis is that Hong Kong’s own food culture, once so inventive, is now fading fast. Many factors are at play: generational change, economic pressures, shifting tastes, and fierce competition.

Too often, when an old shop closes, social media dismisses it: ‘It deserved to close. Bad service, poor quality, overpriced.’ That mindset is part of the problem. These closures are not just about individual business failing; they are about a cultural fabric unravelling. The loss affects all of us, not only cultural advocates, but diners, owners, and the city as a whole.

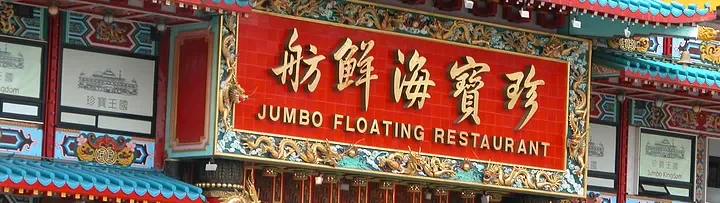

Every week brings new headlines about closures. Crowds rush in at the last minute to ‘check in’, to post photos, to ‘mourn’. But our streetscapes, habits, and way of life are disappearing at breathtaking speed. Dai pai dongs (大排檔) are nearly gone. Neon signs, once the city’s visual language, now survive only in museums and exhibitions. Even icons like 珍寶海鮮舫 (Jumbo Floating Restaurant) have vanished. Traditional crafts stand on their last legs: boatbuilding, 艇仔粉 (sampan noodles), bamboo scaffolding, the life of the Tanka people. Preservation often stops at documentation — photos, interviews, books — rather than keeping practices alive.

So the question is not only how do we preserve our local culture? But also what kind of Hong Kong do we want, and what kind of future?

This is not just about government. Every Hongkonger has a role:

When was the last time you visited the old shops in your own neighbourhood?

On a hot day, would you still sit at an outdoor dai pai dong?

When buying snacks, do you choose a local bakery’s egg tarts instead of trendy international bakehouses?

Or are you among those who only rush in once a closure notice is posted, to ‘mourn’ and ‘check in’?

And to the owners of old shops

Are you maintaining food quality and service, or relying on tourist traffic while treating locals with indifference? When young people express interesting in apprenticing, are you willing to pass down your craft?

As for the government

For over twenty years it has dismantled neon signs, only to resurrect them in crude LED imitations under schemes like ‘Night Vibes Hong Kong’. It suppresses street hawkers, while Singapore successfully secured hawker culture as UNESCO intangible heritage. It let Bruce Lee’s former residence be demolished, despite his global stature. Even bamboo scaffolding, once admired worldwide, is now under threat.

Hong Kong already has powerful cultural assets to promote itself. But instead of valuing them, resources are poured into generic mega-events that other cities can easily replicate.

I am glad to see the Hong Kong Tourism Board promoted cha chaan teng culture abroad, such as at Art Basel Paris 2024. But what does it mean to promote them overseas while they are disappearing at home?

Learning from Sally Lunn’s

Yes, the crafts of making milk tea and egg tarts have been inscribed as intangible cultural heritage. But to preserve Hong Kong’s lifestyle and food culture, it is not enough to protect single dishes. What we need to safeguard is the whole social and cultural setting — the cha chaan tengs and bing sutt, and dai pai dong. Social history and culture should remain alive. Waiting until everything is on the brink of extinction, then locking it away in a museum display, is not preservation.

There are already people and groups offering guided tours of old eateries. But what else can we do? Could Hong Kong’s cha chaan tengs and bing sutt learn from the model of Sally Lunn’s, finding ways to keep their culture both alive and sustainable?

I know Hong Kong eateries are small and crowded; we cannot turn them into museums like Sally Lunn’s. How can long-standing cha chaan tengs better maintain food quality? How could we think more creatively?

Let’s not wait until they vanish from our streets, leaving us only photos to reminisce, or obituaries to mourn closures.

Why It Matters

Hong Kong’s food culture is not just about taste; it is about memory, belonging, and continuity. Each cha chaan teng and bing sutt carries decades of ordinary lives within its tiled walls and faded menus. Preserving them is not only about nostalgia but about recognising their value as living heritage.

What survives today deserves our attention — before the next chapter of vanishing eateries is written too quickly. From bing sutt to cha chaan teng, what comes next? What space is left for Hongkongers to carry forward their creative and inventive spirit?